Learning about the past through graveyards...

If you’ve ever visited a graveyard, did you wonder about the stories behind the person buried deep beneath that plot of earth — their last resting place? Who did they leave behind or what did they accomplish while they lived — or how did they die? I believe everyone has a story that they leave behind and the stories that people who lived in Arizona, especially while it was considered just a territory (Arizona became a state in 1912), have pretty amazing stories. Its rugged landscapes and lack of law made for pretty rough survival.

There are so many differing stories about the Pleasant Valley War that there is hardly enough room to write everything or anything about it to truly project the causes and results of its story here. Was it a feud between two families -- the Grahams and the Tewksburys -- or a feud between the sheepherders and the cattlemen? Not only do they question how the war started -- or why it started -- but each historical account is told from witnesses from one or the other sides of the families involved — with a large portion of it from oral history. From the many books I have read, written by knowledgeable and trusted researchers, it is hard to determine the basis for such a bloody battle that took place in the Tonto Valley of the Arizona Territory between 1882 and 1892. According to Jynx Pyle’s book “Pleasant Valley War” and several others, “the ones who knew the most didn’t talk about it” and many of the witnesses to this decade-long war took a lot of the information with them to their graves.

The gist of it, however, is that the Graham brothers of Iowa and the Tewksbury family of California (via Maine) moved to Pleasant Valley to take advantage of its lush pastures and abundant land to raise cattle. What started out as a friendly union turned into to a family feud which was worse than the more famous Hatfields and McCoys. It was much bloodier and, from what I can gather, it was over a joint effort to steal someone else’s cattle that went sour. It precluded a battle over the grazing of sheep and cattle when a sheepherder was shot and killed. It resulted in a lot of people getting shot and killed. The story is fascinating and the Museum -- located in the town of Young -- holds many of the tragic historical accounts in text and photos that can only be appreciated by visiting it in person. The graveyard just outside of the Museum is a reminder of the bloody war.

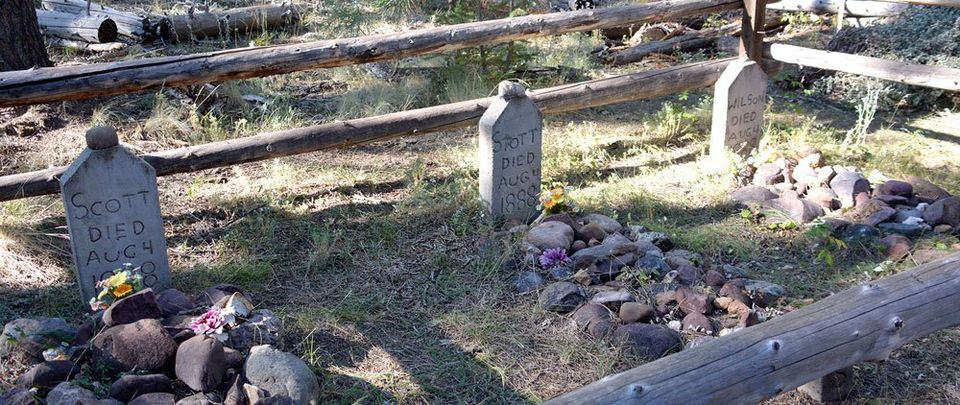

One of the many casualties of the Pleasant Valley War was the hanging of three young men — Jamie Stott, Jimmy Scott and Jeffery Wilson.

According to the book, “Black Mesa; The Hanging of Jamie Stott” by Leland J. Hanchett, Jr., Stott had come to Arizona from Massachusetts via Texas where he learned the ropes of raising stock — mostly horses. His father, a prominent businessman who worked for Talbot’s Woolen Mill out East, was bank rolling most of his adventures and investments. After a few years in Texas, his father’s boss, Thomas Talbot, made it possible for Jamie to get a job with the Aztec Company in Arizona. To qualify for a job at the Aztec Company, you had to have a sponsor. Since Talbott owned some stock, he would guarantee Jamie a job. In June of 1885, Stott left Texas and drove about six stallions from Texas to Arizona, accompanied by his friends, Thomas H. Tucker and William Jefferson Wilson. It took them four months. Unfortunately, by the time Stott reached Holbrook, Arizona, Talbot had died and, without a sponsor, he wasn’t able to get a job. Instead, he looked for land in northeastern Arizona near the Mogollon Rim and bought out the original settler of the Aztec Springs Ranch as well as the Bear Springs Ranch and his father gave him $1,000 to buy horses and cattle (a lot of money at that time).

Here, too, the story about what happened is clouded with many different tales and witnesses who, at the time, wouldn’t speak for fear of losing their lives. Some people claimed Stott was a horse thief and others spoke very highly of him. Others say they hung him for his land. According to Pyle’s book, the horse thief trail ran very close to the Aztec Springs Ranch and Stott had friends who worked for the Hashknife Outfit — the Aztec Cattle Company out of Holbrook. In Hanchett’s book, Jamie’s sister, Hannah, mentions a threat by Deputy Houck to Jamie when he stated that he would “be running his sheep on Jamie’s land one day.”

On May 5th, a store belonging to Captain Watkins in the Tonto Basin was robbed by two men and the thieves were followed to Graham’s ranch(although Stott claims to have remained neutral in the feud, he tended to stay on the Graham side). On May 30th, three men were shot in the Tonto Basin and, according to the St. John’s Herald, several men were told to leave the area and never come back — one of the men’s names was Jamie Stott. Stott stated that he had never been in that part of the Tonto Basin where the robbery took place and he felt that Houck was trying to turn the citizens of Tonto Basin against him. After another incident, involving Jake Lauffer, a friend of the Tewksburys, Houck declared that it was the work of Jamie Stott, Jimmy Scott and Jeff Wilson (a Hashknife cook and cowboy) even though Jimmy Scott was held prisoner at the Perkins Store during all of these incidents.

On August 11th, 1888, Houck and some other men rode to the Aztec Springs Ranch where they found Jamie Stott, Jeff Wilson, Lamotte Clymer and Alfred Ingham (Clymer and Ingham had been staying with Stott for the summer). Houck placed Stott and Wilson under arrest even though he failed to produce a warrant saying he had left it in his coat pocket at the Bear Springs Ranch where he had stopped the night before. Another group of men showed up with Jimmy Scott. All in all, there were 25 men. Jamie made everyone breakfast before they left (Obviously, he didn’t have a clue as to Houck’s intentions). After breakfast Houck manacled the three, Stott, Scott and Wilson to their horses and rode toward the old Verde Valley Road (also known as FR 300, the Rim Road or the General Crook Trail) where he stopped under a ponderosa tree. They put nooses over the heads of Scott and Wilson, removed the manacles and then drove the horses out from under them. After watching his friends, Stott wanted them to undo the manacles so he could take on all of them. They tied a red bandana around his neck first and then they put the noose over his head. They would pull the noose tight and then let it loosen as if they changed their minds. They would lift him up and down several time until at one point they hung him too long and he died. Then they drove his beloved horse Coyote away.

They left all three bodies hanging until three days later, a cowboy on his way to Pleasant Valley discovered their bodies and reported it to authorities. Jamie’s parents received the news on the 16th of August and they traveled from Massachusetts and were at the Aztec Springs Ranch on the 24th. Jamie had already been buried. His horses and cattle were sold to another rancher for pennies on the dollar and the Stott family never received any compensation.

The graves of Jamie Stott, Jimmy Scott and Jeff Wilson can be seen on the “Black Canyon Journey Through Time Auto Tour” in the Chevron-Heber Ranger Districts in the Apache Sitgreaves National Forest. It is Number Seven on the route and is located just off Forest Road (FR) 300. There is a Forest Service sign.

Following the FR 86 through the Black Canyon south of Heber, there is another gravesite. It is the old homestead of the Baca Family. The Baca Family Cemetery is located 9.9 miles on the Black Canyon Auto Tour along FR 86. It is Number Six on the Tour and is on the right side of the road as you are heading toward Black Canyon Lake. The Baca Ranch was built in 1889 by Juan Baca Y Montano and his wife Damasia Torres. They had seven girls (all beautiful) and one boy. In September of 1903, Juan died and his son, Fred, became the man of the house at age 15. Because of the seven daughters, however, many eligible bachelors stopped by the Baca Ranch. John Nelson, who owned a sheep ranch west of Heber married Mollie Baca in 1998. He built a road from his sheep ranch to the Black Canyon Trail during their courtship so he could knock an hour off his travels. The Baca Ranch was the center of social life in the area. The Bacas loved to dance and held several parties every year.

When we stopped at the gravesite while driving the Black Canyon Auto Tour (a self-guided tour), Jerry Elliott came over and asked us if we had any questions about the gravesite. As it turned out, Elliott is a direct descendent of the Baca Family and he was up visiting the old homestead — something he does every year. In fact, Jerry is the grandson of Lucy Baca Prince and his mother, who was born on the property around 1923 — and who married an Elliott — is still alive at 97 years old.

Jerry Elliott told us that they homesteaded 40 acres but leased thousands of acres from the Forest Service to raise cattle. All seven girls worked the ranch and were considered cowgirls. We followed Jerry over to where the main cabin once stood. Originally there were five cabins not including the main house. Every time a girl was born, Juan would build another cabin and connect it with a hallway. After Juan died, they tore down all of the cabins except for the cabin his mom was born in. They used that one as a cook kitchen.

We listened and imagined the old house as Jerry described it. When you came to the back porch and you looked to the left, you would see the basement; take two steps up and you would be on a the landing where they kept the milk cans. Two more steps up and you would be in the kitchen which was located in the back corner of the house. The back porch faced the creek and they spent most of their time in the backyard, gardening and other activities.

When Jerry visited, as a kid, they would just bring bedding and food and sleep in the old house. Eventually, the place succumbed to vandalism and the Family had the Forest Service tear it down. You can still see the remaining foundation and Jerry gave us a tour of the other empty meadows where barns and other cabins once stood. Even the old well that his Great Grandpa Baca dug is still there. “It was 30 feet deep and full year-round,” he told us. There was an enclosure around the well area and the original handle is still there. He told us that they would do all of their washing there.

Close to the well, there is a large hidden cave. “I had always heard about it while I was growing up,” Elliott explained. “and when I was about 21, I set out to find it." When he finally did find it, all of the dishes of his mom’s childhood tea set were still in there. They were all lined up. “Everything was there and nothing was broken,” he said. Jerry removed them and they are now in a display cabinet at his house. He would take his grandkids up to the cave and they would take pictures of them inside it. Eventually, his grandkids grew up and they all wouldn’t fit in the cave anymore. Now, every year, they leave money in the cave to see if anyone ever visits it. So far, the money is still there.

Across the creek is a flat area with green grass where the old barn stood. One of the ranchhands was smoking one night and burned it to the ground. When his Grandma Lucy took them there later on, she told them where the tack room once was and they found about 15 gallons of liniment, horseshoe nails, bridles and a variety of other tack supplies. When the barn collapsed, it folded in and the items in the tack room were spared.

Jerry informed us that we were standing on the last of the original road. “The original road came right up to the house then it skirted the graveyard,” Jerry states. “then it went around the base of the hill just past the graveyard, out toward the elk enclosure and then out to Nelson Canyon.” There is a little wooden bridge in an aspen thicket and that was on the way to where his Aunt Mollie and John Nelson lived in the next canyon.

In the end, Jerry’s Great Grandma Baca sold the ranch to the Schusters. She had bought sheep by mortgaging the ranch and the bottom fell out. Fortunately, her daughter Josephine had married a Schuster and they moved in and helped her, bought the place and then let her live there until she died. The Schusters were the last owners.

Jerry comes every year to check on the old homestead, especially the graves. He has built a large enclosure around the graveyard to protect it from vandalism but mostly from falling trees. There are four graves — including Fred Baca, Juan Baca, Damasia Baca and Dora Baca and a marker for Charles Filippone (Uncle Chuck) who was married to Mary the daughter of Lucy. Although Fred’s headstone is in the Baca cemetery he is actually buried in Lebanon, Oregon. He was the only boy born to Juan and Damasia. Charles’ ashes have been distributed in the Pacific Ocean. Dora, the youngest Baca daughter, is buried there. She died of pneumonia when she was only 18.

We were pretty lucky to have met Jerry Elliott the day we visited the Baca Family Gravesite. Sometimes the stars line up just right, I guess. We are truly indebted to him for giving us great insight into the lives of the great settlers of the Arizona Territory.

Check out more about the Bacas in Leland Hanchett, Jr.’s book, “The Crooked Trail to Holbrook.”

There is also a small graveyard located behind Charlie Clark’s in Pinetop with gravestones dating back to the early 1800s. Its inhabitants include some of the first pioneers to set foot in Pinetop. The Adair family, for example, has about 17 family members buried beneath its vintage gravestones including John Washington Adair and his wife Cynthia (Penrod) Adair.

John Washington Adair was born February 10, 1874, in Kanab, Utah to George Washington Adair and Emily P. Tyler. In approximately 1895, John Adair settled in Pinetop — Arizona Territory. Family members recall that when John rode into Pinetop, he had planned to spend the night and leave the next morning. He stayed, however, and met his future wife, Cynthia Jane Penrod. He established what he called "The Ranch,” which was located about four miles south-west of Pinetop on the old road to Lakeside. They lived there until Cynthia got scared to stay by herself while John was working in Whiteriver. John loaded and drove freight supplies such as food and grain on wagon teams which carried the supplies from Whiteriver to Fort Apache and Holbrook three times per week.

Read more at: www.findagrave.com/memorial/10412800/john-washington-adair

Learning about those who came before us can give us a new perspective on our home territory.