...the myths and the man who lived them

Text and most photos by Annemarie Eveland

Who was DeGrazia? His birth name was “Ettorino” (little Ettore) which means in Italian/Old Greek “to restrain,” or “to defend, hold fast, be steadfast.” It was wise to name him that, for his life would need such strength and devotion to his purpose.

He was born in the small mining town of Morenci, and in his family, the men worked in the mines. His family migrated from Italy and worked very hard to raise their seven children. When the mines played out, they went back to Italy for five years. As Morenci mines activated again, they returned.

As a young boy, he first painted Indian faces, learned the Apache language, and loved roaming the mining hills with his Apache friends. In early school, his teachers couldn’t pronounce his name Ettore, so he was dubbed “Ted,” which followed him through his life. Since his family moved back to Italy for five years, he forgot how to speak English and had to repeat first grade. So, when he finally graduated from high school, he had a beard!

He followed his family’s work in the mines but was witness to mine disasters, fights, brutality, and sad groups of women outside awaiting news of who died in mine accidents. He held steadfast his desire to do something else. When the Great Depression came, he decided to go to school at the University of Arizona. To pay for tuition, he entertained with his trumpet in a band and did odd jobs while studying music and art. He met his wife Alexandra, married, and worked at her in-laws’ movie houses in Tucson, and then in Bisbee.

While traveling to Mexico once, he managed to meet artist Diego Rivera who took him on as a student assistant. To learn art, he slept in the streets, with only a few cents a day to live on. He went to the Market of Thieves where peasants came to buy stolen goods — a place of poverty and despair. So, his early work was about what he experienced, peasants, Mexicans, beggars, fights, and tequila. During the bloody Mexican Revolution he saw soldiers firing upon people they lined them up against a wall. DeGrazia cared very much about these people, and his work reflected the truth he saw, though people didn’t want to buy such tragedies. He also worked for well-known artist Jose Orozco who helped display his paintings, which earned favorable Mexican reviews. So, when he returned to the United States, he felt success was now possible. But, unfortunately, people in the States found his art to be morose and deeply dark. He went back to the University of Arizona and got two undergraduate degrees and a master’s in Art. By then he had well over a hundred paintings, but no place to show them. So, he purchased a small property and built his studio in Tucson.

His artwork completely consumed him. Consequentially, his wife felt estranged and filed for divorce and child support, which he honored.

He had produced so many paintings, he put them out on the street with “for sale” signs, forgot, and left them there. Nobody even stole them! But he was undaunted. Arizona Highways did some articles on his work. And then he met Marion Sheret. They stayed together for the rest of his life. She took charge of the business of his art, the home, and his children, and was steadfast in her efforts to see him achieve his goals.

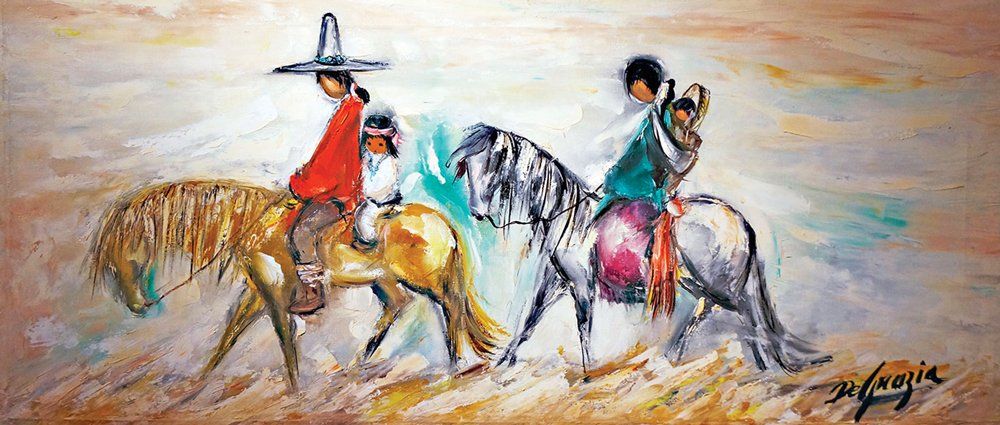

Finally, in the late 1940s, he changed his art style, using a palette knife, lighter colors, and happier scenes. Now he portrayed children, horses, angels, and Indians. A lithographer reproduced his art, and it became affordable for more people. This time, he was well-loved and had many showcases. The southwest themes were very popular, and his success lasted the rest of his life.

DeGrazia began to promote his work with a flair! He was a mix of humor, kindness, anger, generosity, and his appearances became very animated, like showing up with a bottle of scotch and spiking punch bowls at gallery events, spending hours talking with people, as he was donned in his usual trademark of western clothes and traditional cowboy hat.

In the 1950s he bought ten acres near the Catalina Mountains and built several buildings including a chapel which he painted murals inside of and left always open to the public. This gave him a place to sleep, work, and sell his art, as well as a place for prayer. He also received acclaim from a National Geographic article and NBC’s coverage.

Soon, he got more success in 1960 when a Hallmark agreement put his work on Christmas cards. Unicef also asked to reproduce his painting of eleven Indian children “Los Ninos” for holiday cards, which resulted in five million boxes being sold. The following years in the 60s and 70s brought more fame and fortune to him. By the mid-1970s hundreds of thousands of visitors had visited his Gallery.

Gallery of the Sun started to be built in 1965 using Yaqui friends to fashion the adobe bricks. This was a huge 16,015 sq. ft. building. It included paintings of the Indians, as DeGrazia loved history, he wanted to document the Indian ways before they were lost forever. He was also making lots of money from painting and mass producing his children, burros, flowers, fiestas, and Indians. His gallery became a steady stream of visitors, friends, artists, and parties. But he continued to paint every night, unable to sleep, saying he felt close to his creator in the night quietness.

However, his fame and fortune came to an abrupt awakening when he learned that for all his unsold paintings the IRS would tax his heirs. Earlier he had been told he could only take off the actual cost of his paints and the canvas on his taxes. He was furious. His birth name “to defend and be steadfast” came again to support him and he made a daring plan to deal with the situation.

So, one day to protest inheritance taxes on his art, DeGrazia hauled about 100 of his paintings on horseback into the Superstition Mountains, and with Weavers Needle in the distance, made camp with 20 other friends who accompanied him. DeGrazia had made many rewarding trips before into the Superstitions searching for lost gold and hidden treasures. But this trip was different. The next morning, he cleared an area, making a rock fire ring, and a teepee-style large fire. Since IRS said he could be sent to prison if he “pretended” to burn paintings. Many photographers were on hand photo-documenting his burning of the 100 paintings.

In the distance, cliff dwellings towered above them. He felt the ancient ones would be witnesses also. Apache swords, Yaqui deer headdresses, and rattlers were laid on the ground in respect. It resembled a cremation ceremony. At high noon, DeGrazia began burning his paintings and only stopped when it was nearly dark. Taking a sip of Chivas and water, he said: “It is done.” His friends left to sleep, but the artist still sat staring at the ashes, stirring them a bit to make sure all fragments became ashes. It appeared to friends as though he was destroying his own children-a very emotional experience for him.

This 1976 infamous event was reported by The Wall Street Journal and People Magazine, becoming part of the “DeGrazia legend.” DeGrazia was quoted as saying, “I want to be notorious rather than famous. Fame has too much responsibility. People forget you are human.”

Before his death in 1982, he established the DeGrazia Foundation to ensure the permanent preservation of his art and architecture for future generations, provide relief from tax collectors, and keep his gallery alive.

His death was a painful time emotionally for the many who loved him, consuming his time with doctors, radiation, and chemotherapy which did not abate the prostate cancer which spread to his spine. Even in his weakened condition, when he was entreated to charge admission to his gallery, he whispered faintly, “No, there will never be a charge to see my work in the gallery.”

About 600 people attended his funeral and flowers covered his entire grave and gallery grounds. I especially liked that this renowned artist had such a downtrodden beginning, but found a way to make something very remarkable and meaningful out of his life with his art.

Later, some stones from the Morenci mines were piled on his grave. As time went by, the gallery staff saw many stones were missing, and then they noticed that visitors would often put a stone in their pockets. So, the gallery had a dump truck bring another load of stones! I imagined that DeGrazia was smiling at that dump truck delivery and very pleased by all the people who were touched by his life.